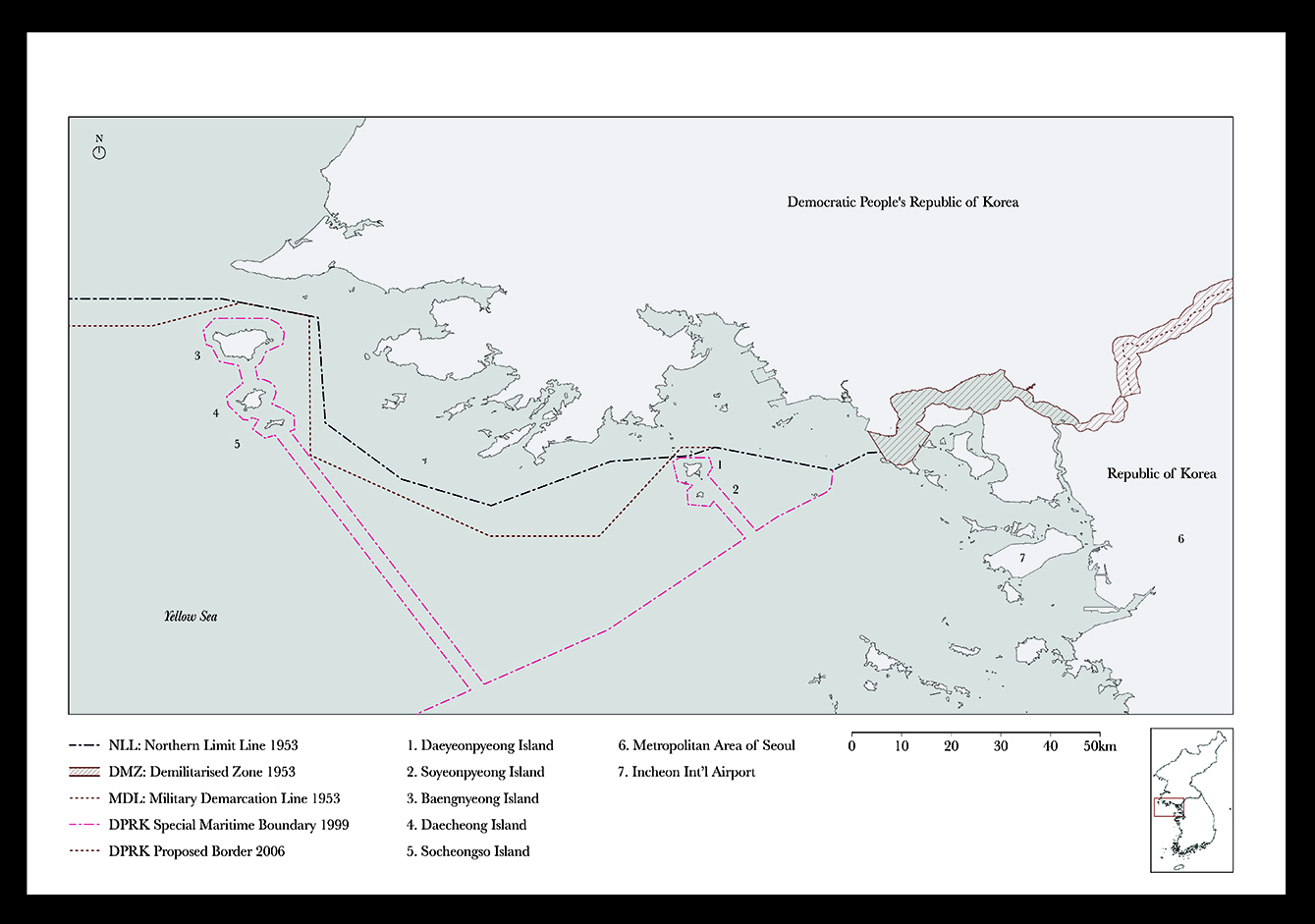

Since the end of the Korean War in 1953, South Korea has faced permanent diplomatic pressure because of intricate relations with its neighbors, China and North Korea. In the aftermath of the war, a rural exodus prompted the exponential growth of its capital city. Nowadays, Seoul is a global metropolis, but because of the country’s geographical and geopolitical confinement, it has struggled to expand both its urban fabric and its productive hinterland. As a consequence, South Korea has shifted its geopolitical agenda to focus on the oceans. This has not been in vain—the country has rapidly and strategically spread a myriad of maritime productive facilities such as artificial reefs, sea ranches, and marine forests, thus giving form to the nation’s obsession of becoming a twenty-first century maritime pioneer.

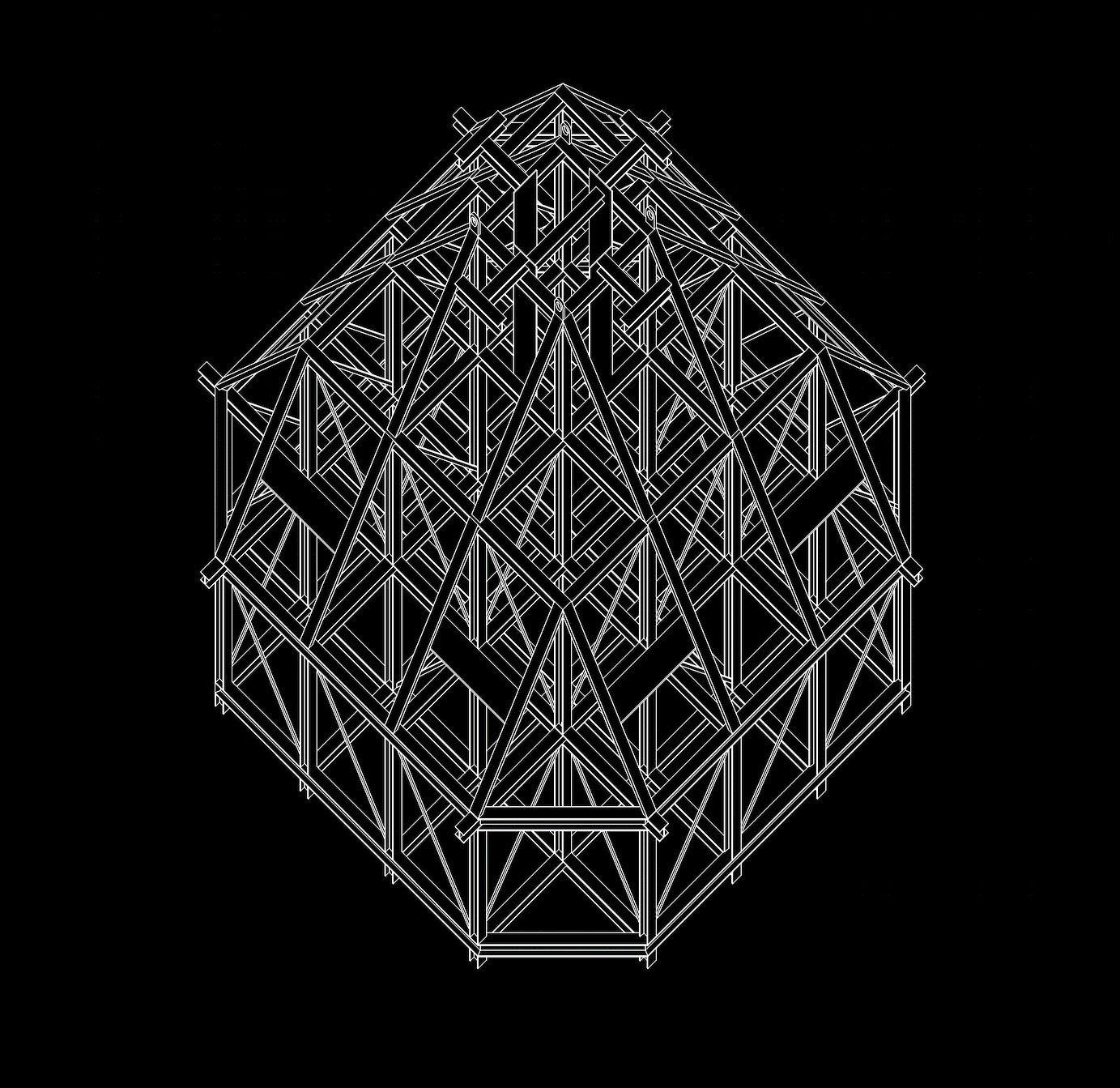

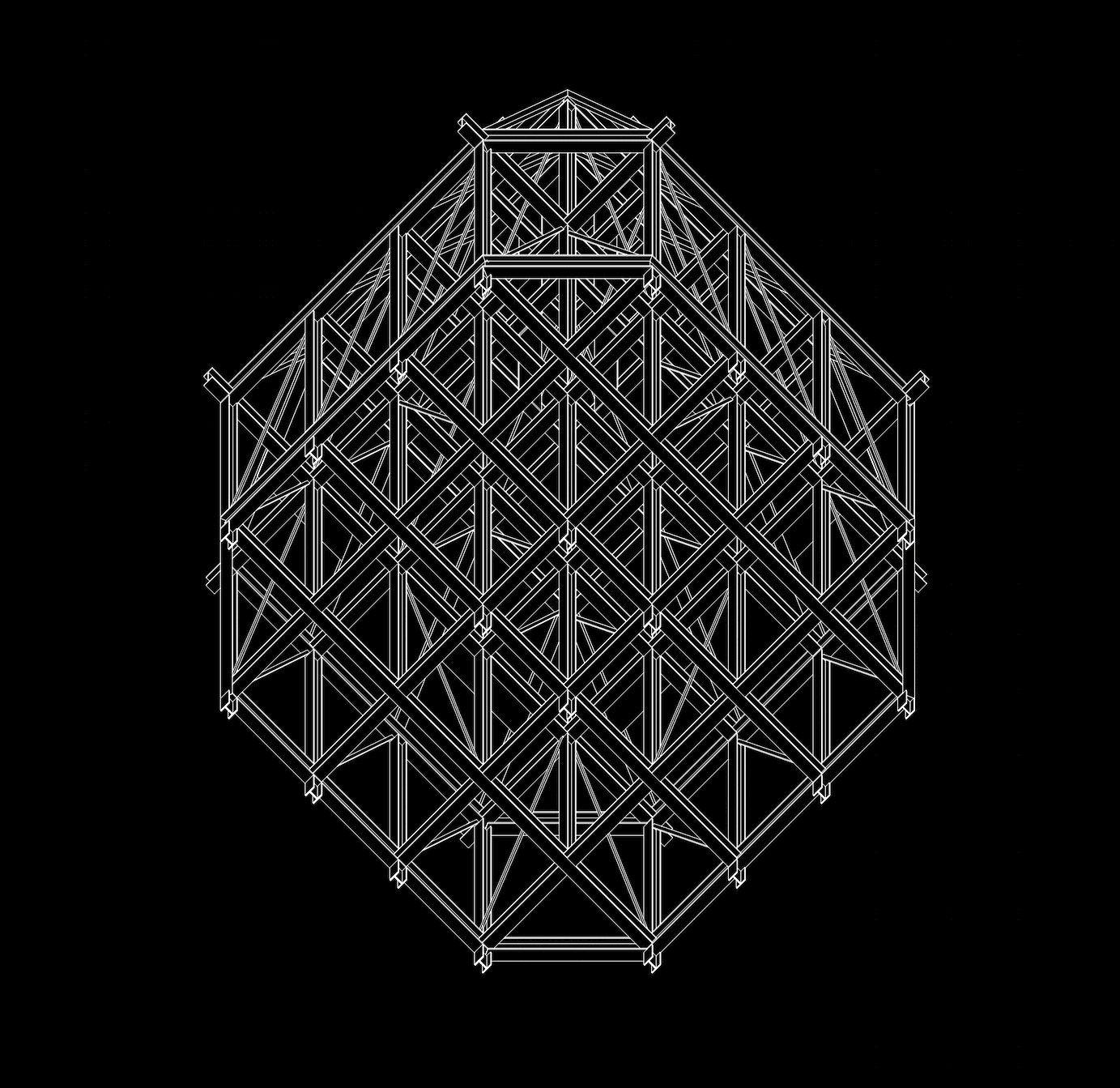

An archipelago of artificial reefs extends the city into the seabed and expands the country’s urban condition beyond the coastline in the form of a nature-culture continuum. These invisible structures host marine life and are designed to progressively degrade. Beyond their infrastructural role, they also perform as cultural, geopolitical, and architectural artifacts, organizing both human and nonhuman bodies under selective conservation, mass production, and defense premises across multiple scales.